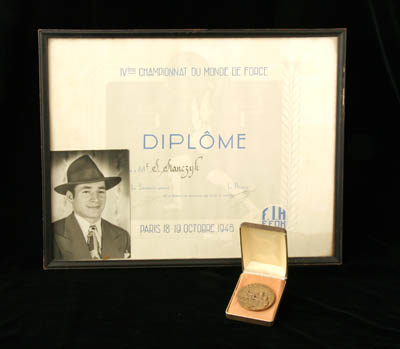

Stanley Stanczyk

Description

Inducted June 13, 1991

Reared in the tough Polish neighborhoods on Detroit’s west side where he took up weightlifting as a matter of survival, Stanczyk went on to win the first of six consecutive world titles in 1946, taking the 148-pound lightweight title in Paris. He successfully defended his title the next five years: 1947 (as a middleweight) through 1951 (as a 181-pound light-heavyweight). In the 1948 Olympics in London, he won the Gold Medal, following up with a Silver Medal in the 1952 Helsinki Olympics. He won bronze medals in world competition in1953 and 1954 before retiring. Stanczyk opened a bowling alley in Miami, Fla. He approached that sport with the same intensity as he did weightlifting. He rolled over 20,000 games, averaging 190.

INDUCTION BANQUET PROGRAM STORY — June 13, 1991

A Survivor of the Fittest

By: Don Horkey

It wouldn’t be accurate to describe Stanley Stanczyk as a “Polish Charles Atlas.”

He was much, much more. Atlas was a bodybuilding devotee who made a fortune peddling his philosophy of physical fitness through mail orders.

Kids of two or three generations ago may recall the ads in magazines or comic books relating how a 90-pound weakling, fed up with getting sand kicked in his face by a bully, gained his vengeance by becoming a disciple of Atlas’ “dynamic tension” fitness program.

But for all of his physical perfection, Atlas didn’t win six consecutive world championships in weightlifting or a Gold Medal and a Silver Medal in the Olympics.

Stanley Stanczyk did.

He became a weightlifter as a matter of survival growing up in the rough and tough Polish neighborhoods on Detroit’s west side.

“We were so poor,” recalled Stanczyk, “my clothes were old and tattered. The sisters (at St. Hedwig School, which he attended for eight years) used to send me home.”

To add insult to injury, Stanczyk’s schoolmates taunted him about his use of Polish, a language he learned from his immigrant parents, natives of Krakow, Poland.

His parents originally settled near White Cloud, Wisconsin. Stanley was the youngest of four brothers and two sisters.

Stanley never knew his sisters.

“There was an epidemic in Wisconsin, they both died before I was born.” Their deaths prompted the Stanczyk family to move to Detroit in 1926 when Stanley was one year old. His father did odd jobs, mostly for a bakery, and for a foundry during the war.

Meanwhile, Stanley was occupied with his own war. “I was fighting every day after school. Different kids were lined up, and I’d beat ‘em all. Then the Sisters would beat me up for beating the kids up.”

The nuns were among few people in Stanczyk’s life to beat him at anything.

Stanczyk honed his boxing skills at a neighborhood Boys Club on Livernois near Michigan Avenue. “I used to watch the kids train with weights. I saw how muscular and big they were compared to the boxers. That’s what I wanted – muscles.”

He was 15 years old, but Stanczyk remembered that lifting weights “came easy” for him. “I was pretty strong. After all, for three or four years before I even saw weights, I was doing that Charles Atlas stuff, you know, pitting one arm against another.”

Five months after he started on weights, Stanczyk won a statewide competition. He was on his way to fame and gold.

Two weeks after his 18th birthday and shortly before his graduation from Chadsey High School, Uncle Sam drafted Stanczyk’s muscles and combativeness to represent the U.S. Army in World War II. He got through three years without injury, and with his muscles in tip-top condition, thanks to weights he devised from armor plates.

Six months after his discharge, Stanczyk won his first championship, in 1946 in Paris, breaking the total poundage record enroute to the 148-pound lightweight title.

Stanczyk successfully defended his title the next five years, 1947 (as a middleweight) through 1951 (as a 181-pound light heavyweight).

In the 1948 Olympics in London, Stanczyk won the Gold Medal, decisively beating fellow American Harold Sakata by a combined margin of 83 pounds after three lifts, the largest margin in any division in Olympic history to that time.

Four years later in the Helsinki Olympics, Stanczyk’s bid for a second straight Gold Medal was thwarted by his own “bad mistake.”

Lomakin of the Soviet Union won the gold by a mere six pounds. Stanczyk was ahead of the Russian by 10 pounds after what Stanczyk mistakenly thought was his second lift, but really was his third and final lift.

“It was a mistake on my part,” Stanczyk said about the confusion. “I could’ve beat him with one more lift.”

Stanczyk won bronze medals in 1953 and 1954 world competition before retiring.

During the years after the war, and while he was competing internationally, Stanczyk put on exhibitions for his sponsor, York Barbell Co., of York, PA. He also was co-owner of a gym, training other weightlifters.

With money he saved and had realized from the sale of the gym, Stanczyk opened a 32-lane bowling alley-restaurant-lounge in Miami, which he and his wife, Dorothy, operated for 27 years.

Stanczyk took to bowling with the same intensity as he did weightlifting. For several years he bowled in seven leagues, almost every night of the week. He rolled over 20,000 games, and all of the scores are recorded in a book – “just like I did in weightlifting.”

His lifetime average was 190. He had two games of 289 and 50 of 279.

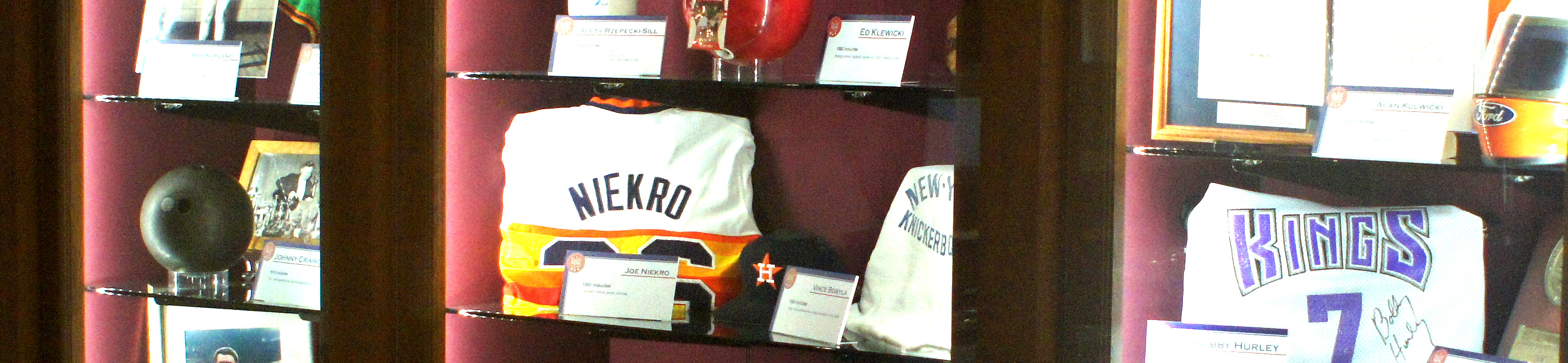

Twice, Eddie Lubanski, a National Polish-American Sports Hall of Fame Inductee of 1978, bowled 300 games in Stanczyk’s establishment, both times on national television.

For 20 years after he sold his partnership in the gym, he used his garage as a training site. Two of his proteg�s got as far as tryouts for the Olympics.

Stanczyk Impresses With Sportsmanship

Stanley Stanczyk impressed audiences at the 1948 Olympics in London not only because of his superior lifting, but also because of his outstanding sportsmanship.

This excerpt from The Complete Book of the Olympics by David Wallechinsky provides a testimonial:

With his third snatch he attempted a new world record of 132.5 kg (about 292 pounds). He successfully hoisted the weight and the judge signaled a fair lift.

However, Stanczyk shook his head and tapped his leg to indicate that his knee had scraped the floor, thus invalidating the lift. Despite this miss, his eventual winning margin of 37.5 kg (83 pounds) was the largest in any division in Olympic history.

Winning the Silver to Stanczyk’s Gold that year was American Harold Sakata, who became a professional wrestler (under the name of Tosh Togo) and later an actor, portraying Oddjob in the James Bond film, Goldfinger.

Stuck in Paris: “Ain’t that a shame!”

Stanley Stanczyk’s first world championship in Paris in 1946 was memorable for more than the Gold Medal he won.

“Planes were on strike. There was no other way of getting home,” he remembered.

“Here we were: 21 years old, just came back from the war, and we’re stuck for two months in Paris. Ain’t that a shame?”

Before he left for France, Stanczyk had signed an agreement with York (Pa.) Barbell Co. to put on exhibitions in exchange for York’s paying for Stanczyzk’s way through college.

“By the time I got back, school was in session and I didn’t feel like going then.”

He did the exhibitions anyway, saving the money he earned to eventually buy a bowling alley in Florida.

Categories

- 1991

- Weight Lifting